As a rather short lived series with a televised run of only six episodes, Gosenzosama Banbanzai (or “Glory to the Ancestors”) is for Mamoru Oshii to what Paranoia Agent was for Satoshi Kon. Not only do these works seem to result from both directors having accumulated leftover ideas and material they originally conceived for other films in the past, but which never actually made it into the final cut, they are also dark satires on the cultural shifts in Japanese society due to western influences on newer generations in foregoing Japanese traditions and embracing a modern consumerist culture. In Ben Hamamoto’s Article on Paranoia Agent, he interprets Kon’s show as a critique on Japan’s repression of atrocities committed by the country during World War II through how the Japanese internalized for their country an innocuous self-image. Hamamoto argues Japan covered over the horrors of its past with the kawaii cuteness culture which arose in the ’70s, during the postwar economic and industrial developments following the time of the American occupation. As Paranoia Agent also seems to critique, there developed during the postwar period a feeling of being victimized by the war that seeped into the Japanese national psyche. The belief of being in a perpetual state of victimhood arose as if it were a psychological epidemic in response to the Hiroshima bomb, a way for Japan to place the blame on other nations rather than the country accepting and taking responsibility for its own involvement in the war. Kon associates this through the American national sport of baseball with Lil Slugger, connoting to the bomb “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima, as a basis for fault finding and grounds for their own victimhood. The plush animal toy Maromi, representing the kawaii subculture, is a means constructed by the Japanese providing them comfort that they are innocent rather than confronting the adversities perpetuated by them in their own society. The willful choice of Japanese youth in failing to undertake their duties to society at large in embracing the kawaii culture, antithetical to following traditional Japanese norms of their forebears in entering adulthood, challenged and changed the nature of Japanese mores with children regressing into childlike states. Satoshi Kon examined this in Paranoia Agent by especially noting how it affects the interrelations of Japanese families with children turning against their parents, who are seen to suffer from a guilt which they have chosen to repress with the same naivete as their children.

Similarly, in the case of Gosenzosama, Oshii also looks to the traditional nuclear family in Japan falling apart from within its own structure due to outside societal influences from the west being brought into the Japanese lifestyle, incidentally changing family relations to where the traditional roles for the Japanese family are led into a fated dissolution. What is particularly interesting in Gosenzosama is that Oshii starts each episode off with a small prelude similar to a wildlife documentary that also provides a foreshadowing to what will develop in the plot for each episode. The comparisons made between nature and the tumultuous family dynamics for the Yomotas suggest Oshii finds the family dissolution in Gosenzama being more derived from fundamental forces found in nature, what constitutes man, rather than being based on any external cultural forces having an impact on one’s duties to the family in Japanese society. However, Oshii does still play upon this latter theme to some degree.

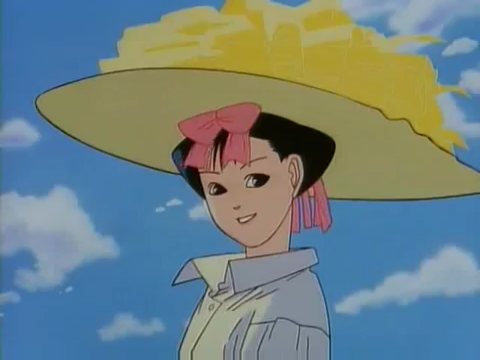

An abandonment of Japanese traditions is evidenced with the adolescent Inumaru and his granddaughter Maroko, who claims to have traveled from the future with the desire to meet her ancestors and who also develops a romantic relationship with her own grandfather. Specifically, the yellow wide brimmed hat Maroko wears when first introduced in the series became a popular fashion style for women in Japan during the ’20s, what was not fully integrated into Japanese society until its transition into modernity with the “moga” (or the modern girl). The “moga” is described as being not so different from the “flapper” of the jazz age in ’20s America in embracing leisure and entertainment in hanging out at cafes and taking on a more liberal sexuality. Oshii seems to even indicate this in the apartment Maroko and Inumaru live in, where can be seen a suggestive poster pinned above the mirror Maroko is adjusting her hair in front of. Additionally, Maroko is seen changing into modern outfits throughout the series from assuming girlish clothing to donning contemporary swimwear, and incidentally she also changes from her demure childlike appearance in the first episode to a more sexually mature and suggestive woman later on. Although in earlier episodes she expresses herself as if she was a Japanese housewife in serving Inumaru and his father, and Maroko is later seen in the series taking the role of a waitress in a restaurant that resembles the basement bars from WWII. Maroko’s sudden shifts from modernity to traditionalism in the series seems based on the same transitions from modernity to traditionalism and back to modernity throughout the twentieth century for Japan. With the coming of the moga being prevalent in the early twentieth century, Japan nevertheless went back to traditionalism and adhered to classic gender roles for women after the country embraced extreme nationalism during its Great Depression, what is also believed to have led the country to joining the Axis powers. Japan’s pre-war nationalism seems attested in Gosenzosama when Inumaru’s mother vows to solidify the family once again and then does a Nazi salute with “Seig Heil” heard on the soundtrack.

As Maroko is thus being portrayed throughout the series as one representing the modernization of Japanese conduct and customs, she also seems to represent one who wishes to please her ancestors and partake in their traditions. Maroko is thence a paradox unto herself. Her image cannot logically exist in Gosenzosama, but only in the minds of the Yomotas does she actually take any real form. Considering how her appearance changes with each episode in relation to the struggles experienced by the Yomotas and what Inumaru desires of Maroko, she serves as a reflection for the Yomotas in yearning to honor Japanese tradition but nevertheless having the desire to forego traditionalism and embrace modernity. Inumauru, who is driven by his own selfishness and seen to also rebel against his forebears, brings Maroko into his home at his parents’ protest. What he also brings onto the family threshold is the threat of paradoxes, or glaring cultural differences between western individualism and the eastern cultural values in putting the group before the self that incidentally leads to a disunion within the family.

Another prominent detail in Gosenzama relating to western influence is the countryside surrounding the Yomota family home, expressing the growing urbanization for Japan during the mid-twentieth century. In the first episode of Gosenzosama, the Yomota’s home is enclosed by wide pastoral grasslands, but then in the second episode the greenery disappears as the land suddenly resembles a desert. While the Yomotas are having dinner, a construction tractor can be seen in the background roaming across the infertile rural-like terrain with Coca-Cola billboards and skyscrapers being built around the Yomota family home. Coca-Cola was introduced into Japan with the occupation of U.S. troops. Considering Coca-Cola is associated with western troops coming in from overseas, it is thus befitting that Coca-Cola cans are mainly seen littering the beaches in Gosenzosama, insinuating how American culture became awash on Japanese shores. An interesting scene attesting this is where Bunmei plays a poignant tune on a piano situated on a pile of Coca-Cola cans that resembles more of a pyre, singing with lyrics like “May 3, useless and bulky stuff” (perhaps a scathing undermining of Constitution Memorial Day in Japan, which takes place on May 3rd) to “a fascism called freedom, a nihilism which finds shelter in peace” (maybe a possible critique of Japan’s illusory pacifism Oshii will later comment upon in Patlabor 2). It thus seems Bunmei laments the changing conditions in Japan as seen through Oshii’s perspective. Furthermore, Coca-Cola was onetime seen negatively by the Japanese in the ’80s that seems to also be tied with the kawaii culture and the Japanese views of America, for the Coca-Cola advertisements conveyed “the implicit message that Coke was a drink for indolent youth, not necessarily for industrious students or hardworking adults. They were likely to dismiss the commercials as irresponsible propaganda….To the Japanese, American workers appeared lazy and self-satisfied, and the ‘I Feel Coke’ commercials only reinforced that view.” When considering Bunmei’s lyrics also mentioned “His ‘black list’ includes the Bible…anarchy is his faith…A guard dog lost in the wind barks in the middle of his confused thoughts,” statements that are not too far off in describing Oshii himself in regards to what he has been politically and religiously affiliated with, what Bunmei’s solo seems to be channeling is Oshii’s own troubled thoughts in wanting a return to traditionalism but finding this objective in vain when confronted with the reality of Japan’s inevitable and irreparable subjection to modernity.

Moreover, a particularly esoteric theme that relates to preserving tradition over modernity in Japanese society in Gosensozma is the incestual relationship Inumaru and Maroko are having while the mother disappears and the father is seemingly abandoned with his sanity deteriorating over the course of the series. In a study conducted by Kubo on incestual relationships in Japan, he found “that there were still rural areas in Japan where fathers married their daughters when the mother had died or was incapacitated, ‘in accordance with feudal family traditions.’ Kubo concluded that incest was considered ‘praiseworthy conduct’ in many traditional rural families. In the 36 incest cases he studied in Hiroshima, he found that there was often community moral disapproval of the families who lived in open incestuous marriages, but that the participants themselves did not think of it as immoral. In fact, when the father was unavailable to head the family, his son often took over his role and had sex with his sister in order ‘to end confusion in the order of the home.’ Other members of the family accepted this incest as normal.” At the end of the series, as Inumaru appears burdened by the guilt in having brought a dissolution to his own family, he tries to return back to his homeland but is only to perish in the snow with the thought of Maroko only on his mind while a yellow butterfly is briefly seen superimposed over his head. The color yellow in Japan can be symbolic for nobility, and the butterfly has been traditionally representative of womanhood and also used for Japanese family crests. Inumaru’s desire for reuniting with Maroko thus seems to suggest his wish to reestablish and preserve the existence of the Yamota clan through bonding with his own granddaughter.

This consolidation of familial ties in Gosenzosama is also based on the star birth mark found imprinted above Inumaru and Maroko’s buttocks. Oshii might have based this idea of a birthmark establishing one’s identity in being part of the family clan on what are called “Mongolian spots.” As explained by two dermatology researchers, “Some scientists believed that presence of Mongolian Spots in Mongols, Japanese, Chinese, Turks, Koreans, Hungarians etc. reflected a common Central Asian origin of these races whereas others in Mongolia believed that Mongolian Spots in other populations was a legacy of the invading armies of Huns and Mongols, thus ‘implicating Mongolia to be the cradle of the Eurasian civilization.’” The Mongolian Spots essentially raise questions as to the exact origins of the Japanese race. When taking into thought the short wildlife segments at the beginning of each episode in Gosenzosama, what Oshii may be suggesting is that one’s self-identity does not truly define one in relation to what ethnic or cultural group they self-identify with, but it is from what is more fundamental and absolute, which is one’s nature.

As Inumaru exemplifies contemporary Japanese youth abandoning the cultural traditions of their forefathers and indulging in their own freedom from obligations in seeking out entertainment and leisure, he harbors his own expressed fears in inevitably becoming his father and decides to retaliate against this role in irresponsibly wasting his father’s money on a baseball bat. In response, his father takes out a golf club while Inumaru threatens him with his bat, both striking fighting poses where Inumaru comes to channel the very concept of the samurai besuboru (or “samurai baseball”). After baseball was introduced to Japan during the Meiji era (around the late nineteenth century), it is believed that it also adopted the way of the “bushido,” or the code of the samurai. This is further portrayed by Inumaru in that he is seen with his hair tied up in a style that resembles a samurai top knot, which is then later in the series seen outgrown while Inumaru lives like a street vagrant, reminiscently similar to the changes in hair style for Megane in Urusei Yatsura: Beautiful Dreamer, another Oshii film that critiques the kawaii culture. Oshii has employed such a “samurai baseball” archetype with Yoshikazu Fujiki’s character in Assault Girls and also with “Crying Inumaru” in The Amazing Lives of the Fast Food Grifters.

Donald Roden has been oft-quoted that baseball for Japan “in 1896 ‘nourished the traditional virtues of loyalty, honor and courage symbolized in the ‘new bushido’ spirit of the age” and further “nourished those values celebrated in rural Japan and the civic rituals of state: order, harmony, perseverance and restrain.’” What Oshii is perhaps conveying with these “samurai baseball” characters in his work is how western influence has transfigured the classical archetypes found in Japanese culture to where they assume different meanings by taking on new modern forms, thus creating a paradox within Japanese self-identity and raising questions as to its authenticity. As a side note, the very theme of reversing the role of the samurai was probably best expressed in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill when Hattori Hanzo states to Uma Thurman’s character, “Funny, you like swords…I like baseball,” before pitching a baseball at the Bride, who slices it in half. This is a not so subtle subtext an American is stripping away one’s own culture after assuming the role of the Japanese samurai, thereby reversing the cultural ramifications from westernization in reasserting the way of the Bushido warrior. This can also be seen in Shinichiro Watanabe’s Samurai Champloo, where the leading characters compete against American seafarers in a game of baseball.

Thus, in similitude to how Kon explored in Paranoia Agent this concern as to what it means to be Japanese anymore in a society which has exchanged its past and tradition for modernity and urban commercialization, what Oshii likely intended to show in Gosenzosama is that the only way one’s placement in modern Japanese society can be understood is through how one has been displaced from it. Of course, based on Oshii’s own biography in finding a place to belong and an ever questioning of self-identity, this can be argued as the leitmotif of his work. His films and personal thoughts derive some inspiration from the introduction of western culture offsetting the Japanese adherence to traditionalism, converting their old forms of conduct and cultural norms into new ones, such as embracing individualistic behavior to partaking in American consumerism and the patronage of corporate iconography. Like Inumaru’s mother calling for a more “realist drama of family life,” Oshii also does not seem to rely on subversive antics in upending this new culture so much as he is attempting to provide an accurate portrayal of modern Japanese life as based on one where western influence has significantly changed it even if he has chosen a more expressionistic aesthetic. In comparison to how Oshii lampooned Japanese traditions in Urusei Yatsura by juxtaposing Japanese cultural norms against its own myths, Oshii renders Japanese culture into a stage play in Gosenzosama for better realizing its form through the limits of its own expression. In displacing the subject from the object, Oshii is able to transform these subjective experiences for his own culture into the more objective and be able to hold it up for his own Japanese audience under a closer scrutiny. This is further denoted in the very character designs through how Oshii accentuates Inumaru and Maroko’s segmented joints, what are not so different from the flexible, angled joints of wooden mannequin-like models used by animators when drafting the anatomical motions for their characters. The theatrical enables Oshii a greater sense of control in expressing the roles of the father, the son, the mother in Japanese society in putting them up on a stage. He replicates the roles for these characters like theatrical puppets, reenacting the family structure for no other reason but to lay witness to its eventual debacle.

Sources Referenced:

- https://sittingonanatomicbomb.com/2010/08/27/the-true-brilliance-of-paranoia-agent-and-why-its-all-about-the-bomb/

- http://apjjf.org/-Robert-Whiting/2235/article.html

- http://www.samurai-archives.com/tme.html

- http://hubpages.com/art/japanese-butterfly-art

- http://www.ijdvl.com/article.asp?issn=0378-6323;year=2013;volume=79;issue=4;spage=469;epage=478;aulast=Gupta

- “For God, Country, and Coca-Cola” (2013) by Mark Pendergrast

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_girl

- “American Multinationals and Japan: The Political Economy of Japanese Capital Controls, 1899-1980” (1992) by Mark Mason

- http://psychohistory.com/articles/the-universality-of-incest/

- http://color-wheel-artist.com/meanings-of-yellow.html

- http://www.ijdvl.com/article.asp?issn=0378-6323;year=2013;volume=79;issue=4;spage=469;epage=478;aulast=Gupta

I could never read this much into a story and while I am not sure if your analysis makes sense, it was interesting to read.

LikeLike