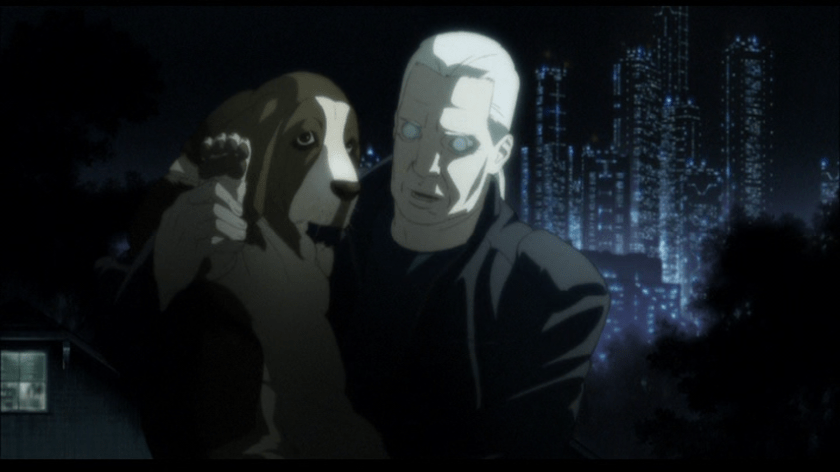

While Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner served as an influence for the first Ghost in the Shell film, even more influence seemed invested into its sequel Innocence. In particular, Oshii seems to have taken inspiration from the use of eyes in Blade Runner and Roy Batty’s quest for longevity (and perhaps immortality), both channeling a possible religious subtext regarding the Buddhist’s path to Enlightenment. Although the question mainly still debated by Blade Runner fans is whether Deckard is a replicant or not, this mystery seems to not matter at all if the central idea director Ridley Scott was aiming for was to follow both Roy Batty’s and Deckard’s spiritual journeys. Both hero and villain seem to eventually become “enlightened” as to who they really are (regardless whether they identify as a replicant or not) once their mortality is fully made apparent to them as the only reality that is enduring and true for them. This is in likeness to Batou and Togusa coming to terms with this same reality as they undertake their investigation into the gynoids. Aside from Deckard, it seems Oshii might have taken inspiration from the villain Roy Batty and J.F. Sebastian (who, like Togusa, is more human, more empathetic and emotionally responsive than the replicants he befriends) when returning back to Batou and Togusa in the sequel, especially when Batou’s character design changed to having white hair and wearing darker clothing like Roy’s character.

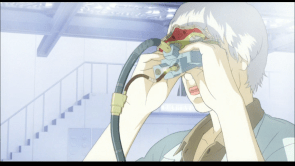

The eyes in Blade Runner have received various religious interpretations, and perhaps one involves the Buddhist belief that reality is illusory and it takes a heightened perception to see a truer and more ultimate reality. In Innocence, Batou’s augmented vision can see all the information that composes his surroundings and so it serves to function as if it were his “Third Eye”, which in Buddhism is symbolic for a “spiritual awakening of knowledge and wisdom.” In Blade Runner, Roy Batty tries to find a way to meet Tyrell, essentially his godlike “creator”, in hopes to finding a way of overriding the 4-year life span that his body is designed to last. He seeks out information from the bioengineer Chew, who designs eyes, and Sebastian, both technicians recognizing Roy as a replicant based on their engineered features, especially their eyes. Likewise, in Innocence, Batou seeks out one of his familiars, Lin, in order to get information as to where Kim can be found. In reaching Kim, Batou and him enter into a discussion regarding immortality that Kim seems to believe he has attained in having transferred his cyberbrain into a doll’s body. Like Roy finding out from Tyrell there is no way to redesign him to have more life, Batou also realizes that technologically prolonging life is just an illusion.

With the prevalent use of eyes in Blade Runner, Scott emphasizes the replicants’ fabricated eyes using red lens flares beaming into their eyes for distinguishing the replicants from the humans. In Innocence, there are similar moments where eyes are seen glinting, such as Haraway’s computer monitors flashing off Togusa’s eyes. The emphasis on Togusa’s eyes particularly seems important when his perception of events is constructed on what he organically, and thus naturally, sees, whereas Batou seems to see Togusa’s illusory humanity in its virtuality through his prosthetic eyes. Blade Runner also plays on such a conflicted use of perception between Deckard, who only knows the replicants from a distance based on the information he gathers from photographs and police debriefings, whereas Roy Batty seems to have more enhanced vision with his engineered eyes. Additionally, when the replicants are put under observation by their human examiners to test whether they are replicants, they are looked at through an eye-like Voight-Kampff machine, suggesting that the humans’ perception of the replicants is just as artificial as the replicants’ eyes. As one commentator points out for Blade Runner, “Tyrell and Chew give the Replicants vision, enabling them to form identity, adopt a perception and to form their own memories and visions.” The gynoids in Innocence have prosthetic eyes that do not seem to give them organically natural or augmented vision. With fabricated green eyes, they are free from perception and thus free from any sense of self-identity and self-consciousness.

The connections between Blade Runner and Innocence are further noted in the scene when Roy talks to the eye engineer Chew and says to him, “if only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes”, suggesting that he is trying to broaden Chew’s perception in getting him to realize his own manufactured humanity. In Innocence, the forensic specialist Haraway is seen in a freezing lab, much like Chew’s lab. The human characters (Togusa and Chew) can feel the cold but the biorobotic characters (the replicants and Batou) are unaffected. Some of the gynoids in Haraway’s lab are seen with hollow eye sockets, and there is also a shot showing their green prosthetic eyes suspended and swirling in water, which seems like a nod to the scene in Blade Runner with the glass of boiling eggs the replicant Pris reaches her hand in to show her endurance to Sebastian. The emphasis on this detachment of eyes in Innocence suggests the gynoids’ sight is not necessary for affirming their existence when perception only gives rise to this illusory subjective sense of self like the replicants in Blade Runner.

Other specific shot comparisons with Blade Runner include the voight-kampff scope showing the orange coloration in Rachel’s eyes while Deckard runs the test on her to determine if she’s a replicant. In Innocence, there can also be seen faint orange lights radiating in the gynoid’s eye while it is under forensic examination. Another important use of eyes in Innocence is the entrance to the gynoid ghost dubbing on the ship, which looks like a giant eyeball that is “awakening”.

Another interesting use of eyes in Innocence is the fact the forensic specialist Haraway has green eyes like the gynoids, indicating her sight and vision is fabricated as well but nevertheless her perception of events is not necessary for her to have any true “knowledge” of the events with the gynoids. Haraway makes mention of child rearing with young girls and dolls to Togusa and Batou, indicating that maybe Haraway already intuitively knows why the gynoids are self-destructing is due to the gynoids possessing the souls of young girls. It is interesting to further note that when Togusa leaves Haraway after their discussion, her fake green eyes lift back in order to look at footage of what may be the gynoids’ interior using an electronic visor. Later on, Togusa is then seen trying to hack into the gynoid manufacturing ship with a visor covering his eyes.

The theme of severed sight and displacement of eyes is noted in Blade Runner when the replicant Leon Kowalski places artificially engineered eyes on Chew’s shoulders with his hands seen holding artificial eyes. This becomes only more thematically significant when Deckard is later attacked by Leon and is almost killed when Leon tries to pierce his eyes using his hands. And then later on when Roy kills Tyrell, he pushes his fingers beneath Tyrell’s glasses, killing his own creator by breaching through his own technological lens and disillusioning him of his own godhood to reaffirm he is just another mortal human.

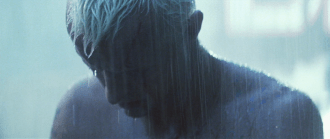

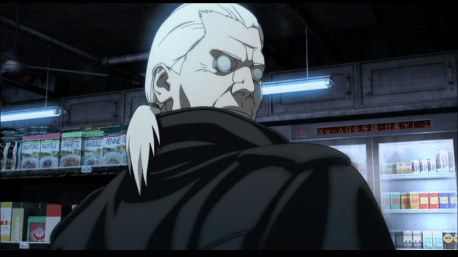

With these riffs on eyes in Blade Runner, Oshii might have considered a potential theme of Buddhist enlightenment as present in Scott’s film. He perhaps chose it as an influence when making Innocence in expressing how one internalizes what one projects onto their peers and close relations as based on choosing what they want to see in others that contributes to creating one’s self-identity. As an armed cyborg with enhanced vision, Batou seems to consider himself invincible. With his habitual trips to the grocery store, it stresses the mundane rituals in his life to where his very choices have become operatic. It is not until he shoots himself in the arm, and seems to experience pain, when he realizes the ultimate reality of his mortality and breaks himself out from his own preconceptions as an enduring machine.

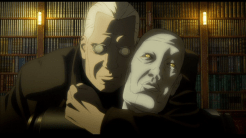

Batou comes to suspect that perhaps Kim hacked his cyberbrain, and so maybe this also means Kim has been wielding him like a puppet and thus Batou is Kim’s creation. The narrative keeps it open as to who might be fully in control over Batou’s choices in Innocence when considering he is influenced primarily by the information that he receives through his augmented vision, and thus leaving open who is actually “creating” him in reanimating him. It is Kusanagi who ultimately frees Batou from Kim’s virtual traps in sending the message of “death” to Batou, almost as if she, a pseudo-deity who has attained her own technological immortality, is freeing Batou from his implied fascination with immortality in getting him to realize it’s a lie. Likewise, the scene between Tyrell and Roy in Blade Runner seems to have been an influence for Kim when Batou disillusions Kim that he has attained godhood in his freedom from the body and from relations in his isolation in his mansion. It seems to allude to Roy Batty disillusioning Tyrell of his status of godhood in his own solitude in his ziggurat tower. It is also notable that in both sequences, Roy and Batou’s more human allies, Sebastian and Togusa, are both watching from afar in unease at these confrontations.

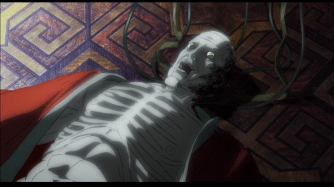

After both Roy and Batou come to see there is no “truth” (the key to immortality) to be found, there is a similar homoerotic moment of the creation meeting with his creator that is followed by the creator’s death at the hands of his creation. With Tyrell’s glasses and Kim’s prosthetic gold eyes, they are both blinded with their own technological sight in believing themselves to have attained godhood. There also seems to be a similar use of sound effect with the sickening crunch of Tyrell’s eyes and also when Batou subdues Kim’s cyberbrain followed by them both moaning in pain.

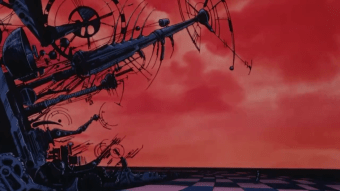

The paneling and sizes of the doors to Tyrell’s bedroom and Kim’s study also look similar in design. Additionally, both Kim and Tyrell are seen with what appear as their life support systems situated next to where they are resting that preserves their life and keeps them seemingly immortal.

When Leon attacks Deckard in Blade Runner, he says to him, “Wake up, time to die”, which is then later repeated by Roy when he says to Deckard, “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe….Time to die.” This parallel suggests that when fighting Leon, Deckard seems averse to admitting what he does not want to see, which is his death. However, when fighting Roy, Deckard has a moment of pause and sympathy in seeing Roy’s humanity as Deckard sees his own mortality in Roy. Innocence ends in a similar manner where Batou sees Kusanagi, who has become distant to him throughout the film, leaving him once again as if Batou is again laying witness once more to Kusanagi’s death when he saw her prosthetic body get shot up in the first film. With these conclusions, both films convey that it is not until one witnesses the death in a familiar does one “wake up” from the illusion of one’s own life.

A notable scene in Innocence that seems to visually communicate that all existence is more relational than it is individual is the spiraling tower for the police headquarters in the northern district that Batou and Togusa journey to in their flight on the carrier. The tower definitely seems modeled off the tower for the police headquarters in Blade Runner. An important detail to note are the statues that surround the headquarters. They depict the Chinese warrior god Guan Yu. Guan Yu statues can be found at police stations in Hong Kong, and are said to be associated with brotherhood, loyalty, and self-identity through group solidarity. Additionally, Guan Yu has importance for foreigners visiting different regions in China, since “among the overseas Chinese community, the temples dedicated to Guan Gong [or Yu] also demonstrated how the traditional social ideals provided a model for migrants as they leave their homeland to seek opportunities.”

That Batou and Togusa venture to the northern’s police headquarters with Guan Yu statues accentuates a sense of brotherhood thematically contrasted with the social fragmentation found at their own jurisdiction’s police headquarters they visit earlier in the film. The police officers in their jurisdiction are seen working at a distance from each other in their cubicles, their work environment stressing a disunity in a socially alienating setting. Also note that the holographic projections of the officers during their debriefing with Chief Aramaki concerning the Yakuza, some of the officers are taciturn and distant in standing from one another. It provides a real sense these officers do not even exist as they never interact or speak to one other. This lacking sense of a brotherhood on the police force is also denoted by the tense exchange Togusa has with an officer who seems to comment on Section 9’s arrogance in interfering with their investigations. The officer particularly mentions to Togusa an adage on persimmons, which “in Buddhism, the persimmon is used as a symbol of transformation. The green persimmon is acrid and bitter, but the fruit becomes very sweet as it ripens. Thus, man might be basically ignorant but that ignorance is transformed into wisdom as the persimmon’s bitterness is transformed into sweet delicious fruit.” Togusa’s expressions of anger in Innocence always result either with his frustrations with Batou’s recklessness to whenever he is confronted with the reality of his own ignorance. Togusa is always affronted by the very thought of being nothing other than a lifeless doll.

Subliminals

While the background details in many films can be of incidental aesthetic choice or recycling old footage and animation for production convenience, filmmakers have the tendency to take the opportunity in deliberately including hidden messages in their work. With the amount of creative control Oshii had on Innocence, this gave him great initiative to include more subliminals in Innocence than he has in any of his other films. Subliminals are often defined “below the threshold of consciousness”. They are images influencing the unconscious and then later are made fully conscious to the viewer without one realizing it. The approach is thematically true to Innocence when its main conflict is centered on this disparity between self-consciousness and that which has none, the underlying innocence to all consciousness. The very process of analyzing, drawing associations, and making deductions itself plays upon the viewer’s sense of consciousness. Considering humans are unconscious 95% time and only conscious 5% of the time, Innocence completely stays true to this fact in playing off of how actively unconscious humans really are while consciously processing the information they see. Below are some details in Innocence that could be taken as possible subliminals.

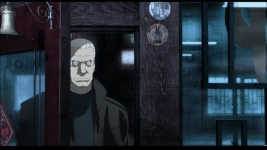

At the beginning of the film, when Batou first makes his grand entrance and steps out of his car, one can see a lit sign with the word “Life” with the red outline of a heart shaped around it. Oshii has thought of Innocence centering on Kusanagi’s loss to Batou as a loved one reflecting a sense of life from those who are now dead, remarking, “The affect that a person leaves behind is the evidence that they have lived.”

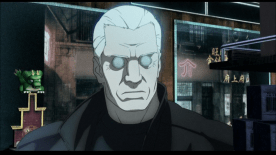

When Batou walks into the alleyway to eventually confront the gynoid, his enhanced sight passes by a poster hidden in shadow that shows a gilded bird with a golden laurel arched beneath while it is seen soaring to a circular blue-white disc set above it. This seems to serve as a subliminal for the golden bird in Kim’s manor.

As Batou returns home and opens his fridge, there can be seen “Silver Pitcher” labeled on a green bottle. Batou chooses only the “Stray Dog” beer can as that is the only thing he seems to drink. The “silver” on the green bottle may be setting the viewer up for Kim’s mansion where Batou’s dog is reproduced as a silver animatronic figure lying on an emerald green floor. Additionally, In the Fan Wan Ching, which provides precepts for Japanese Buddhist clerics, it “prohibited the selling of liquor, a restriction which was applicable only to laymen since monks were not allowed to touch gold or silver.” As the film suggests, Batou is akin to a Buddhist monk in his religious journey, so it is appropriate then that Batou drinks beer with “Stray Dog” labeled but doesn’t seem to touch the silver bottle and seems to not be at all allured by the beautiful gold interior in Kim’s mansion when seeing it as an illusion.

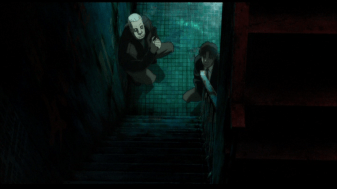

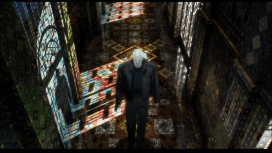

In the first half of Innocence, there are many shots of streets and narrow corridors with patterned tiles covering the columns, the walls and floors of various establishments, such as the elevator Batou and Togusa ride in and also the Wakabayashi. Note particularly the scene where Batou is returning home. He enters in and out of shadow while tiled flooring can be seen behind him. This seems later paralleled with the strange mosaic corridor in Kim’s manor.

Before Batou shuts the door, one can briefly see outside a digital clock that reads 12:30 p.m. Entering in the store, Batou passes by a box labeled “Midnight Dreams” that is set next to containers of tea bags. It is also interesting to note that Togusa is later seen drinking tea in Kim’s manor. In Masaki Yamada’s novelization of Innocence, Batou has late night dreams of having a son. This play on dream states and alternative realities is further indicated with the checkerboard flooring in the store that alludes to Alice in Wonderland. Another detail to take note by the store’s door is the sticker of a rabbit. This is returned to later with the revolving globe in Kim’s mansion where a rabbit can be seen with the other animals. The rabbit could be a small reference to the Buddhist tale of “The Selfless Hare” or possibly the white rabbit from Alice in Wonderland.

A “No Entry” sign can be seen on the steel door from where the Yakuza “crab man” emerges and then later on we see the same “No Entry” symbol on a sign in the convenience store that seems to prohibit stacking any cans there. In addition to these common details, there is a diamond shaped sign on the front doors of the Wakabayashi and the store; there are television screens seen near the outside of the Wakabayashi that is showing the same footage as the television in the store; and there is also checkerboard flooring in both the Wakabayashi and the store. These parallels between the Wakabayashi and the store suggest Batou’s battle against the Yakuza is an illusory battle and thus in vain. The Yakuza were not his real enemy in the grand scheme of his investigations but actually himself on a spiritual level. Batou seems to come to this very realization when believing it was Kim who hacked his cyberbrain and not the Yakuza.

The Doll Head that is worn during Chinese New Year festivals is earlier seen in the convenience store in a picture for a toy vending machine. Additionally, one can see what looks like a toy green dragon on top of one of the vending machines, and then later green dragons are seen imprinted on the flags that are part of the uniforms for the parade attendees wearing these Doll Head masks.

While looking around Volkerson’s house, Ishikawa lifts a portrait of a leaf set next to what looks like a funerary candle. This could be a subliminal for the use of fallen leaves at the parade festival, where there is felt a sense of grief.

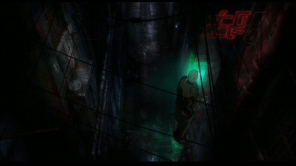

One last interesting detail to note is the use of fluorescent lights earlier in the film. When Batou travels into the alleyway, the first feature shown is a flickering red fluorescent light, which seems later echoed with the neon sign of a red Japanese character flickering above Batou as he returns home. Then in the convenience store, Batou looks up to see a white fluorescent light, suggesting his reality has now become more “illuminated”.

Numbers

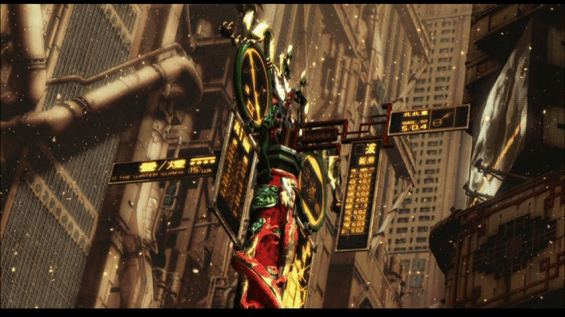

During the parade scene, there is an arcing shot of a street sign (with a large building sign on the far right behind it that features Oshii’s beloved basset hound). The right electric sign seen above is headed with “Sec/M”. Although it seems doubtful, this could be a discreet reference to “Sections” from the Book of Matthew (“M”). For if one compares the chapter and verse numbers from the Book of Matthew with the numbers listed on the sign, it results in a series of Biblical verses involving the Lord’s Prayer that do not logically cohere. Although some of these passages are strikingly synonymous with some of the film’s content and themes:

5:04: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

One of the film’s themes is grief and mourning as Batou is struggling with his own in having lost Kusanagi.

4:03 And the tempter came and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.”

This seems not to relate to anything, but it’s interesting there is a brief shot of Togusa eating what looks like a loaf of bread at a temple.

5:03: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

The “poor” in spirit referring to those with spiritual poverty that relates to material poverty. Batou chooses a moderate living and seems to chastise the illusory wealth that Kim possesses.

6:09: “This is how you should pray…”

4:03 repeated

4:19: “Come, follow me,” Jesus said, “and I will send you out to fish for people.”

The closing song at the end of Innocence is “Follow Me”, which may be in connection to Kusanagi telling Batou to “Follow Me” as his guide.

6:02: “Thus, when you give to the needy, sound no trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may be praised by others. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward.”

This could be describing the parade attendees, such as the Buddhist monk seen in the crowd and there are two festival attendees who are playing trumpets, standing as if they were collectively in a state of ceremonial worship.

7:02: “For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.”

This verse is a befitting description for the use of doppelgangers and mirrors in the film.

6:09: “This is how you should pray…”

5:02: “ And he opened his mouth and taught them.”

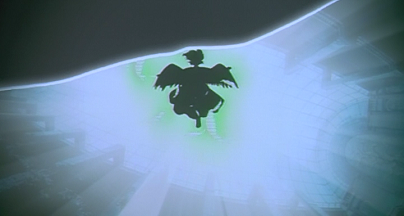

Also note this symbol ( ϴ ) is seen on the top screen right above the one listing these numbers. This could be Theta, which is the Greek letter symbolic with death and also associated with consciousness. Theta has the numerical value of 9. This is interestingly coincidental with the number designating Batou and Togusa’s unit, Section 9. Also notice the number 9 is later seen in the below shot with Kusanagi (inhabiting the lifeless gynoid body) aiming her gun directly at the number 9.

That the above cited symbol is theta seems possible when one notes there are Greek letters mixed in with Japanese characters on a red sign seen above the fridges in the convenience store. As to what message the sign translates to, I have no idea.

When looking at those possible Biblical numbers on the street sign, one can also see Buddhist dragons holding the flaming pearl of enlightenment pointing in opposite directions. While the numbers listed and the dragons are directing different paths, they nevertheless both meet at this same intersection marked with a dragon seen coiled around the sign’s pole. Oshii could be suggesting Buddhism and Christianity having a common theological basis in that they both seek this same spiritual truth to freeing oneself from the material world. In considering Kusanagi quoted from Corinthians in the first film, and she communicates to Batou using numbers like 2501, then perhaps the guidepost is a message to Batou for his own spiritual journey. This possibility seems more supported when one can see briefly scrolling out on the sign to the left the words: “ship to the water surface”, which could be a reference to the gynoid manufacturing ship Kusanagi and Batou finally physically meet or perhaps to the deep sea diving in the first film that precedes Kusanagi quoting from Corinthians.

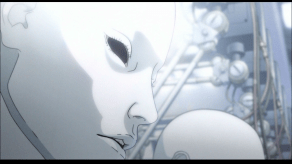

The notion Kusanagi is perhaps communicating to Batou with numbers is supported when she is seen hacking into the ship’s system using a terminal that has numbers scrolling around it. Also notice the above shot has wire cables in the background framed to where they seem connected to Kusanagi’s neck and her cyberbrain. The shot suggests that she communicates through the network using numbers. Another interesting detail is the virus being transmitted by the ship’s A.I. is Type 1052, which is the reverse of 2501, an appropriate countermeasure to Kusanagi’s use of numbers. The future world of Innocence, like the present day world, is one built using numbers, characters and code to convey meaning where every communicative symbol seems easily interchangeable for another. This is in line with Transhumanist thought in overcoming dualism in raising consciousness with technology that also seems to fulfill Nietzschean philosophy, arguing there are no objective values or truths to the world as one must try to seek these actual values outside constructed ones in order to overcome nihilism and see the apparent truer meaning to everything.

Sources Referenced:

- http://www.buddha-heads.com/buddha-head-statues/third-eye-of-the-buddha/

- http://scribble.com/uwi/br/tkarantinos.html

- http://www.chinatownology.com/guan_gong_culture.html

- http://www.answers.com/Q/In_Japanese_symbolism_what_does_persimmon_represent

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subliminal_stimuli

- http://www.simplifyinginterfaces.com/2008/08/01/95-percent-of-brain-activity-is-beyond-our-conscious-awareness/

- Graner, Paul (2000). “Saich: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theta